The coming changes in the International Monetary System: dedollarization, massive public and private debt levels

What was the Bretton Woods Monetary System?

Why the international monetary system based on a fiat U.S. dollar has provided the United States with some exorbitant economic privileges.

Many central banks have been gradually reducing their stocks of dollar-denominated Treasury bills and bonds in their official reserves relative to gold.

In the United States and in other economies, lax fiscal and monetary policies could trigger financial crises and an important economic downturn.

Most Reliable Car Brands

Toyota vehicles are engineered to last well beyond 200,000 miles with proper maintenance, thanks to rigorous quality control at every stage of production and simplified powertrain designs that reduce potential failure points.

Finish reading: https://www.zerohedge.com/technology/toyota-remains-worlds-most-reliable-car-brand-rivian-least

Microsoft AI CEO Warns Most White Collar Jobs Fully Automated “Within Next 12-18 Months”

The man leading Microsoft’s AI sprawling efforts is sounding the alarm over imminent mass labor disruptions, warning that the overwhelming majority of white-collar professional work could vanish to automation far sooner than most business and policy leaders are willing to admit – something we’ve been concerned about since early 2023.

In an interview with the Financial Times, Microsoft AI CEO Mustafa Suleyman forecasted that within the next two years a vast swath of desk-bound tasks will be swallowed by AI.

“I think we’re going to have a human-level performance on most, if not all, professional tasks – so white collar where you’re sitting down at a computer, either being a lawyer, accountant, or project manager, or marketing person – most of the tasks will be fully automated by an AI within the next 12 to 18 months,” Suleyman said when asked about the time table for Artificial general intelligence, commonly known as AGI.

(Tom: And this cam to me this week.)

I strongly suggest that you read it and forward it to those you feel should have the data.

Something Big Is Happening

By Matt Shumer • Feb 9, 2026

Precious Metals Data Of Interest

Run It Hot: Trump, the Fed, and the Coming Currency Debasement https://internationalman.com/articles/run-it-hot-trump-the-fed-and-the-coming-currency-debasement/

Seems like there is a buying opportunity for those who are not risk averse… https://x.com/felixprehn/status/2017961132967731359?s=20

’Rock Now Beats Paper’: Making Sense Of “Silver Friday’s” Utterly Rigged Nonsense https://www.zerohedge.com/precious-metals/rock-now-beats-paper-making-sense-silver-fridays-utterly-rigged-nonsense

There is a veracious appetite from big banks for gold and, in the case of silver, industrial users for the metal. I am still bullish on gold and silver, and my target on gold by 2030 is $10,000 per ounce. https://www.zerohedge.com/markets/never-seen-risk-my-career-ed-dowd-warns

You Are Cause

US Consumer Sentiment and Shares vs Gold

The University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index is one of the clearest windows into how the average American actually feels about the economy.

Each month, the university surveys households across the country, asking straightforward questions about personal finances, job prospects, inflation, and expectations for the future. Those responses are distilled into a single number that captures the public’s economic mood. Because it has been tracked for decades, the index offers a long-running reality check on confidence at the household level.

Today, the University of Michigan Consumer Sentiment Index is sitting near record lows — decisively below levels seen during the 2008 financial crisis, the dot-com bust, and even the deep recessions of the early 1990s and 1980s.

How can stock market valuations be at or near historical highs while the average American is about as pessimistic as they’ve ever been?

This contradiction is a perfect illustration of the financial fun house — and the extreme distortions that relentless money printing has pumped into the system.

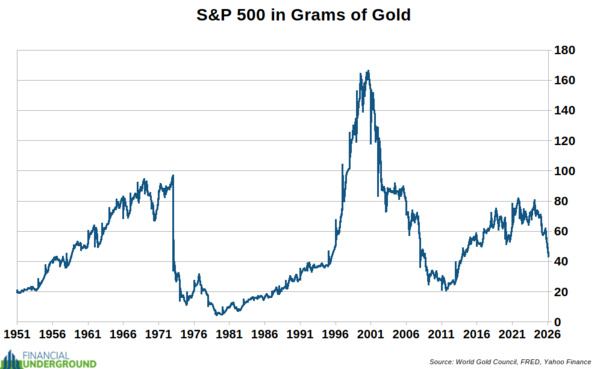

If fiat currency is a dishonest measuring stick — and it is — then how do we accurately measure the stock market?

The best option is to measure value in gold, honest money that no politician can arbitrarily debase.

If measuring in fiat is like looking into a fun house mirror, then gold is a mirror of truth. And when we measure the stock market in gold, that truth becomes clear. Below is a chart of the S&P 500 measured in gold going back to 1950.

Viewed through the lens of gold, the stock market tells a very different story than it does in fiat terms — and this chart makes that unmistakably clear.

The most striking feature of the chart is what isn’t there: a sustained upward trend. The S&P 500 today is worth the same amount of gold it was in 1995.

Despite decades of nominal gains, the stock market has repeatedly given back those gains when measured against gold. In other words, the rising stock market was more a reflection of currency debasement than of real wealth creation.

This helps explain the disconnect at the heart of today’s market. In fiat terms, stock prices appear to be at record highs. But in gold terms — a unit that cannot be printed — the market looks far less extraordinary.

Measured in gold, US stocks peaked in 1999, when the S&P 500 was worth just over 164 grams of gold. Today, the index is worth 43 grams — a decline of more than 73% from its 1999 peak.

More recently, the S&P 500 peaked at about 82 grams of gold in late 2021. Today, it’s worth roughly 43 grams. In other words, despite the recent melt-up and the stock market ripping to new nominal all-time highs, when measured in gold, the S&P 500 is down more than 47% since late 2021 and sitting at roughly the same level it was in 1995.

In other words, when we look at the stock market through a mirror of truth rather than a fun house mirror, it becomes clear that it is in a deep bear market. It’s no wonder consumer sentiment is near an all-time low.

Despite the nominal melt-up in stocks, most Americans are becoming poorer when measured in real, honest money — not fake government confetti.

I expect this dynamic — a nominal stock market melt-up alongside Americans becoming poorer — to accelerate in 2026. I expect the stock market to go higher and valuations to become even more insane — but I expect gold to rise even faster.

Currency debasement is driving this trend, and unfortunately, all signs point to much more of it in 2026.

This is exactly why positioning matters far more than headlines in the years ahead. If stocks continue rising only because the dollar is being sacrificed, then real gains will increasingly come from assets that benefit from that debasement rather than from it being disguised.

Gold has already been signaling this shift — and within the gold space, select opportunities stand to outperform dramatically as this trend accelerates into 2026.

Source: https://internationalman.com/articles/the-melt-up-trap-why-stocks-must-rise-until-the-dollar-breaks/

Energy and Wealth: The Correlation That Built Nations

From an International Man Communique newsletter.

The relationship between energy consumption and national wealth is one of history’s most consistent patterns.

From coal-fired Britain to oil-powered America to today’s renewable energy leaders, access to abundant, affordable energy has been the foundation of economic prosperity. This correlation isn’t coincidental — it’s mechanical. Energy powers industry, transportation, communication, and virtually every productive activity that generates wealth.

The Industrial Revolution provides history’s clearest demonstration. Britain’s dominance in the 18th and 19th centuries directly correlated with its exploitation of coal reserves. Coal powered steam engines, which mechanized textile production, iron smelting, and transportation. Britain’s GDP per capita increased roughly 10-fold between 1750 and 1900, precisely tracking its exponential increase in coal consumption.

Nations without coal access — or unwilling to industrialize — remained agrarian and poor. The energy-wealth gap widened dramatically during this period, creating the modern developed-developing world divide. As an aside, this is how a nation with crooked teeth and zero cuisine could go about bullying and colonizing much of the world.

America’s ascent to superpower status followed an identical pattern, but with oil instead of coal. The discovery of Pennsylvania oil in 1859, followed by massive Texas fields in the early 1900s, gave America an unprecedented energy advantage. Cheap, abundant petroleum powered automobiles, aviation, petrochemicals, and eventually plastics — entire industries that wouldn’t exist without energy density only oil provides.

By 1950, America consumed half the world’s energy and produced half its GDP. This wasn’t correlation; it was causation. Energy powered the factories, transported the goods, and literally fueled American prosperity.

Post-war Japan and Germany demonstrated how energy access drives reconstruction. Both nations were devastated in 1945, yet rebuilt rapidly by securing reliable energy supplies. Germany imported coal and developed nuclear power. Japan, lacking domestic energy, built the world’s most efficient industrial base to maximize limited resources. Both became economic powerhouses not despite energy constraints but by prioritizing energy infrastructure. In fact, this is why supply chains matter. In any event, their GDP growth rates directly tracked energy consumption increases through the 1960s-80s.

The correlation holds in reverse, too…

The 1970s oil shocks proved that energy scarcity creates immediate economic contraction. When OPEC embargoed oil shipments, Western economies plunged into recession. GDP growth rates turned negative precisely when energy supplies tightened and prices spiked. The lesson was unmistakable: modern economies simply cannot function without abundant energy. Prosperity requires power, literally.

China’s recent transformation provides the most dramatic modern example.

Between 1980 and 2020, China’s energy consumption increased 20-fold while GDP grew 50-fold. China went from producing 2% of global GDP to 18% by becoming the world’s largest energy consumer. They built coal plants at unprecedented rates, imported massive oil and gas quantities, and invested heavily in renewables.

Energy access didn’t just correlate with growth — it enabled it. You cannot manufacture steel, operate factories, or power cities without energy. China’s wealth came from energy-powered industrialization.

Today’s correlation remains unchanged. The wealthiest nations — America, Germany, Japan, South Korea — consume vastly more energy per capita than poor nations. Sub-Saharan Africa, with minimal electricity access, remains poor not coincidentally but consequently. Energy poverty is economic poverty.

The pattern is mathematical: energy powers machines, machines amplify human productivity, productivity creates wealth. No nation has ever developed without dramatically increasing energy consumption.

The energy-wealth correlation isn’t just historical observation — it’s economic law. Prosperity requires power, and those who control abundant, affordable energy will dominate economically. It’s always been that way, and it likely always will be.

Editor’s Note: The historical pattern laid out above is unmistakable: energy is the foundation of wealth, and shifts in energy access signal much larger economic realignments.

As the global system moves into a period of tighter resources, rising geopolitical tension, and structural strain, the consequences will be felt first in markets and capital flows.

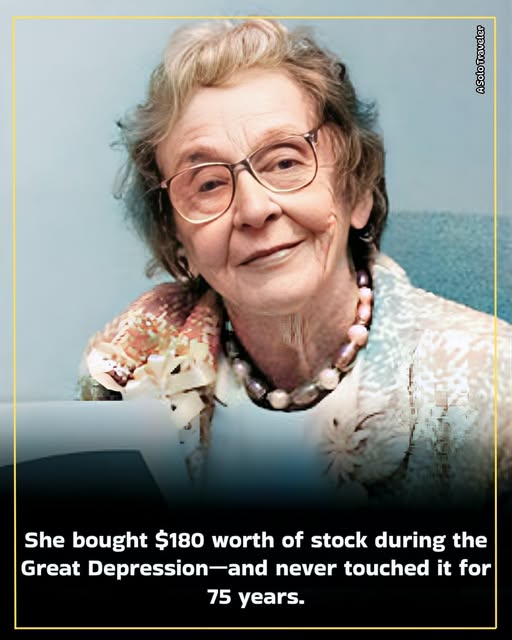

Grace Groner

She bought $180 worth of stock during the Great Depression—and never touched it for 75 years.

In 1935, Grace Groner made a decision that looked insignificant at the time. She was working as a secretary at Abbott Laboratories, earning a modest income in a world still reeling from economic collapse. Women were rarely encouraged to build wealth. Financial independence seemed like a luxury reserved for men with means.

That year, Grace bought three shares of Abbott Laboratories stock for sixty dollars each. One hundred eighty dollars total.

Then she did something radical for the era. She held them.

Grace never chased trends. She never sold during panics. She never tried to time the market. She simply reinvested every dividend the company paid and trusted time to do what individual effort could not.

While markets crashed in the years that followed, she held. While World War II erupted and the economy shifted to wartime production, she held. While the Cold War raised fears and recessions came and went, she held. While other investors panicked and sold, she stayed still.

Her life remained simple in a way that seemed almost stubborn to those around her. She lived in a small one-bedroom cottage that had been willed to her. She bought her clothes at rummage sales. After her car was stolen, she never bought another one—she just walked everywhere instead, even into old age with a walker in hand.

She carried the mindset of someone who had lived through scarcity and never forgot it. The Great Depression had taught her that security came from living below your means, not above them.

Her wealth grew quietly in the background while her lifestyle never changed. Nobody suspected. Not her neighbors. Not her colleagues at Abbott where she worked for 43 years before retiring in 1974. Not even most of her friends.

The stock split. The shares multiplied. The dividends compounded. Year after year, decade after decade, that initial $180 investment transformed into something extraordinary—but Grace lived as though it didn’t exist.

She volunteered at the First Presbyterian Church. She donated anonymously to those in need. She attended Lake Forest College football games and stayed connected to the school that had educated her decades earlier. She traveled after retirement, experiencing the world while still maintaining her frugal habits.

In 2008, at age 99, Grace quietly established a foundation. She never told anyone what it would contain.

When Grace died on January 19, 2010, at age one hundred, her attorney opened her will. That’s when everyone discovered the truth.

Her original one hundred eighty dollars—three shares of Abbott Laboratories purchased 75 years earlier—had grown into more than seven million dollars.

The people who knew her were stunned. “Oh, my God,“ exclaimed the president of Lake Forest College when he learned the amount.

Grace, the woman who walked everywhere and bought secondhand clothes, who lived in a tiny cottage and volunteered her time quietly, had been a multimillionaire the entire time. She just chose to live as though she wasn’t.

And she didn’t spend that fortune on herself in the end.

She left nearly all of it to the Grace Elizabeth Groner Foundation—created to fund service-learning opportunities, internships, international study, and community service projects for Lake Forest College students. The same college that had educated her in 1931, paid for by a kind family who took her in after she was orphaned at age 12.

Grace had never forgotten that gift of education. Now she was paying it forward, making it possible for students who needed opportunity the way she once had.

The foundation her estate created would generate hundreds of thousands of dollars annually in dividend income—money that would change countless lives for generations. Students who otherwise couldn’t afford to study abroad or take unpaid internships would now have that chance because of three shares of stock a secretary bought during the Depression.

Her cottage—the small one-bedroom home where she’d lived so simply—was renovated by the foundation and is now home to two female Lake Forest College seniors each year, living there as Grace’s guests.

Grace Groner proved something that challenges every assumption we make about building wealth.

She proved that you don’t need a high income to become wealthy. She proved that you don’t need to be born with privilege or connections. She proved that you don’t need perfect timing or insider knowledge or lucky breaks.

Sometimes wealth comes from something much simpler: patience, discipline, and the belief that your future is worth investing in, even when the first step looks small.

Three shares of stock. One hundred eighty dollars. Seventy-five years of not selling.

That’s all it took.

But it wasn’t really about the stock, was it? It was about understanding something most people never grasp: that compounding requires time more than money. That the most powerful investment strategy isn’t activity—it’s stillness. That true wealth comes not from what you earn but from what you keep and let grow.

Grace worked as a secretary her entire career. She never became an executive. She never got rich from her salary. She never inherited a fortune or won the lottery or built a business empire.

She just bought three shares of a good company and never sold them.

While everyone else was chasing the next hot stock, the next quick profit, the next get-rich scheme, Grace was doing nothing. And in investing, sometimes doing nothing is the most powerful thing you can do.

Her story forces us to confront uncomfortable truths. How many people earn far more than Grace did but will die with far less? How many chase returns instead of letting returns come to them? How many mistake activity for progress?

Grace Groner sat still for 75 years while the world spun around her. She lived modestly while wealth accumulated quietly in the background. She died having touched more lives than most millionaires ever will—not because of what she spent, but because of what she saved and gave away.

Her foundation estimates it provides opportunities to students generating $300,000 annually in benefits. All from $180 invested in 1935 by a secretary who understood something profound about time, patience, and the power of never quitting.

The next time someone tells you it’s impossible to build wealth without advantages, remember Grace Groner. Remember the woman who bought three shares during the Depression and held them until she was 100.

Remember that sometimes the most radical thing you can do is make a small decision and trust it long enough to prove everyone wrong.